by Catherine Love

At the latest annual session of Devoted and Disgruntled, a forum for those working in theatre to air both passion and frustration, it was telling that one of the busiest groups was gathered around the question “what can we do about touring?” For those in attendance, the question was a familiar one, but the answers were not forthcoming.

As this example suggests, there is evidence of a widespread feeling of dissatisfaction – if not outright disillusionment – with the current model of touring theatre in the UK. The financial strain of taking a show on tour seems to be increasing, with companies shouldering more of the burden from venues, while relationships with the areas and audiences that the work visits are often shallow and fleeting. Something is not working.

This frustration provides the backdrop for Fuel’s New Theatre in Your Neighbourhood (NTiYN) project, an initiative that aims to begin answering just that question: what can we do about touring? The ambition behind the project is to forge better links between Fuel, the work it tours and the areas and communities it tours to. It is about a dialogue with venues and audiences, both new and existing.

“Traditional touring models have been about people dropping into each place, performing and then moving on to the next place. What we’re trying to do is build a relationship with audiences and communities.”

Kate McGrath, co-director of Fuel

While the visiting artists might vary from year to year, the aim is to create Fuel as the link, building a relationship that establishes trust on the part of audiences and encourages them to experience new work. The project also involves work eventually being commissioned specifically for particular localities, cementing the link between the cultural event and the area in which it is taking place, with Fuel sitting at the nexus of these relationships. In the company’s own words: “we want to create a following for our work: one that is sustainable, growing and ever-changing”.

This report looks back at the initial six-month research phase of NTiYN, placing the initiative within the context of the current touring landscape in the UK and sharing its key findings. The hope is that through a combination of research, reflection and shared lessons, it might be possible to move closer towards answering that opening question.

Touring Theatre in the UK

During the discussion at Devoted and Disgruntled, a number of concerns and frustrations were expressed about the ways in which touring theatre in the UK currently works. Companies and artists are perceived to be taking a greater share of the risk than regional venues; fewer resources are available, meaning that the marketing of a show and its engagement with local audiences is limited; theatregoers are booking later, contributing towards a general aversion to risk; touring theatre companies are often denied access to audience data at each of the venues they visit. The challenges are manifold.

This paints a picture that is corroborated by the experiences of a number of touring companies, producers and venue managers. A major difficulty surrounds the simple imperative to attract audiences, which for many companies is absolutely vital to the ongoing viability of their work. As Jo Crowley, producer for theatre company 1927, observes, “there’s a constant frustration about lack of audiences here”. She compares the situation in the UK with the experience of touring internationally, where the company have been met with considerably larger audiences.

It is suggested that the root of the problem lies in successfully connecting work with the right audiences. Gavin Stride, director of Farnham Maltings and one of the key forces behind South East touring consortium House, emphasises the need to “better connect the ambitions of artists with the ambitions of audiences”. This is echoed by producer Ed Collier of China Plate, who states that “touring and making for us are always completely intertwined”, going on to describe how the organisation thinks carefully about audiences right from the start of the making process.

Connected to this question of audiences is the relationship with venues, who should be much better placed to provide local audience insight for touring companies and artists. While in some cases this collaborative exchange does take place, frustration with the overall lack of cooperation from venues is a recurring sentiment. Crowley argues that “there needs to be a better conversation […] about how we work better to collect the information we need and to nurture our audience collectively”, while an Independent Theatre Council (ITC) conference in February 2013 highlighted how difficult it is for touring companies to collect data and information on their audiences from different venues.

Another concern that keeps emerging is to do with the depth of engagement that visiting artists and companies are able to achieve. A phrase that is repeated with startling regularity is “parachuting in and out”, capturing the fleeting quality of many artists’ visits to different venues. Battersea Arts Centre’s (BAC) artistic director David Jubb claims that “there’s no real level of depth of engagement”, while Crowley suggests that the length of time a production is able to spend in an area makes a huge difference. “You can see a distinct difference when you’re in a town or city for a week,” she says.

For Fuel, a further area that they feel needs addressing is the experience of touring for the artists involved. The fleeting nature of visits to venues all around the country can be both frustrating and exhausting, while the financial strain means that many artists have to hold down additional jobs, restricting the time that they can spend making their work and meeting audiences. As well as developing audiences, Fuel feel that touring needs to be made more sustainable and artistically fulfilling for the artists they work with.

The final major area of concern is, unsurprisingly, financial. As both venues and companies face cuts in their public funding, touring artists are being confronted with challenges on all sides. Venues are now less able to take risks, increasingly opting for box office splits rather than paying guarantees, while the pot of funding available for individual touring projects is shrinking. The shared impression of those at Devoted and Disgruntled was that touring is simply more expensive than it used to be.

There is also the knock-on impact of financial difficulties faced by theatregoers, who as a result are booking tickets later and displaying a decreased appetite for risk. As Caroline Dyott of English Touring Theatre (ETT) notes, “there’s certainly an awareness that audiences are being pickier about what they book and booking later so that they can take less of a risk on something”. This all creates an environment in which touring work that is perceived to be experimental or risky presents an ever growing challenge.

ACE Strategic Touring Fund

One attempt to address the current shortcomings of touring, of which there are more than can be fully addressed within the constraints of this report, is Arts Council England’s (ACE) Strategic Touring Fund. This initiative, launched in 2011, is awarding funding of £45 million between 2012 and 2015 to arts organisations offering innovative touring and audience development solutions.

The programme’s stated aims include “people across England having improved access to great art visiting their local area”, “stronger relationships forged between those involved in artistic, audience and programme development” and “a wide range of high quality work on tour”. There is also a particular emphasis on work for young people and on areas, communities or demographic groups classed as having low cultural engagement.

To date, the Strategic Touring Fund has awarded a total of £16,463,673 across seven rounds of funding, with projects spanning a wide range of art forms, target audiences and regions of the country. Alongside NTiYN, the below projects offer a snapshot of how some of the other successful applicants are using this funding to address the difficulties involved in touring.

BAC’s Collaborative Touring Consortium is transporting the theatre’s Cook Up model of new work, food, conversation and debate to six areas of low cultural engagement. This touring programme is designed to work collaboratively with the six partner venues and to generate a genuine artistic exchange, engaging with local artists as well as bringing in work developed by BAC.

ETT’s National Touring Group is linking together a consortium of major regional receiving theatres to offer those venues more agency over the work they present and to create a network for touring high quality, large scale drama, with the aim of developing audiences’ appetite for this work.

China Plate’s Macbeth: Blood Will Have Blood has now completed the initial phase of touring an immersive schools version of Macbeth in partnership with educational organisation Contender Charlie. This project worked with a number of hub venues around the country and brought in students from the surrounding schools, thereby establishing long-term links between education and the arts in those areas. A second phase is currently being planned.

Paines Plough’s Small-Scale Touring Network is working to establish a connected and collaborative network of around 25 venues across England, to which the company will take regular small-scale productions alongside undertaking audience development work. The hope is that more meaningful relationships will be formed between venues, touring companies and audiences.

New Theatre in Your Neighbourhood

“New Theatre in Your Neighbourhood is a pilot research project run by Fuel in order to find new ways of engaging with more and more diverse audiences through touring really exciting and innovative new work.”

Louise Blackwell, co-director of Fuel

The initial six-month phase of NTiYN, funded through ACE’s Strategic Touring Fund and the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, has focused on establishing links with partner venues and developing audiences in these areas. The emphasis at this stage has been on research and exploration, with the aim of taking these findings forward into the project’s future life.

The five venues in question are The Lighthouse in Poole, The Continental in Preston, ARC in Stockton, the Lakeside Theatre in Colchester and the Malvern Theatres. Each of these venues received one or more of the five Fuel shows included in the initiative: Uninvited Guests’ Love Letters Straight From Your Heart and Make Better Please, Inua Ellams’ The 14th Tale, Will Adamsdale’s The Victorian in the Wall and Clod Ensemble’s Zero.

Alongside presenting these shows, each venue was also involved in research and audience development work carried out in partnership with a Local Engagement Specialist (LES) hired by Fuel for their knowledge of the local community. This model was designed to provide Fuel with additional networks and contacts in each of the different geographical locations, as well as supporting their desire to establish a deeper connection with the areas that they visit.

The audience development work undertaken at each of the venues by the LES spanned a wide range of activities, including workshops held by the visiting artists, engagement with local schools and universities, communication with existing arts and community networks, ticket offers and discounts, and the promotion of Fuel’s work at other arts events. Fuel has also been working with Maddy Costa of Dialogue, who ran Theatre Club events at a number of the venues. These informal post-show discussions are modelled on the format of the book club and offer an open space for anyone who has attended to share their thoughts with others.

While the key findings will draw in outcomes from all five venues, for the purposes of this report the focus has been narrowed down to two case studies: the Lighthouse in Poole and the Continental in Preston.

Case Study 1: Poole

The Lighthouse in Poole is a large arts centre, catering for a wide variety of audiences in the surrounding area. Its programme covers live music, comedy, dance, film and visual arts alongside theatre, with the building incorporating a cinema, a gallery, a large concert hall, a 669-seat theatre and a smaller studio space. It is a venue with a wide remit and competing demands on its resources, offering a necessarily diverse programme.

Fuel brought two NTiYN shows to The Lighthouse’s studio space: The 14th Tale and The Victorian in the Wall. Fuel supported these visiting productions through the work of LES Lorna Rees, who undertook a range of audience research and development activities. These included running workshops with the artists, targeting audiences at Bournemouth University with the help of newly recruited student ambassadors, forging connections with existing networks of local artists, and working closely with box office staff. While much of the work done by Fuel at The Lighthouse was successful, there were some programming challenges; the scheduling of the shows, for instance, coincided with a major outdoor arts event in the town and with the university holidays.

Fuel’s most notable successes, meanwhile, were achieved through a personal approach. Eschewing the tactic of offering free tickets in favour of adding value, Lorna explored ways of deepening audience engagement through her “Theatre Salon” model. This was successfully used for the first performance of The Victorian in the Wall, after which audience members were invited to stay behind for free drinks and nibbles and an informal Q&A with the show’s cast. This event was well attended and encouraged lively conversation with the cast, creating a much more relaxed environment than the usual rigid structure of the post-show talk. One couple said that they usually never stay for these talks as they worry it will go over their heads, but they enjoyed the Theatre Salon and displayed an interest in attending similar events in future.

Another small but particularly heartening triumph was persuading two teenage boys to attend The 14th Tale. Lorna approached the pair outside The Lighthouse just before the show, offering them free tickets and signing them up to the theatre’s student membership scheme. After seeing and enjoying the show, the two boys stayed behind to speak to Inua and to thank Lorna for the tickets. As Lorna commented in her feedback, “this is what this project does – it gives us permission, with our depth of knowledge, to make decisions and take risks and to maybe, just maybe, with two judiciously applied comps, convert two teenage boys to theatre-going”.

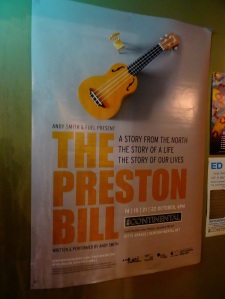

Case Study 2: Preston

The tiny theatre visited by Fuel in Preston makes a dramatic contrast with the expansive, multi-purpose mass of the Lighthouse in Poole. The venue is attached to the back of a pub – The Continental – a little outside the city centre. This space is programmed by They Eat Culture, a small organisation who are involved in organising cultural projects across Lancashire. The Continental itself serves a relatively broad purpose as an arts venue, hosting live music, comedy, spoken word and theatre. As the staff explained to Fuel, music and comedy tend to draw the biggest crowds, while theatre remains more of a challenge.

The only NTiYN show touring to this venue was The 14th Tale, which visited for two successive weekday nights. More difficulties were encountered in this area than in Poole, and despite the efforts of LES Chantal Oakes to bring in new audiences, attendance was relatively low. Once again, planning was an issue; Inua was unable to run a workshop in this area due to schedule clashes, while it has since been suggested that it would have been more sensible to programme one night rather than two. Other challenges included a lack of engagement between the arts scene in Preston and the University of Central Lancashire, stretched resources at They Eat Culture, some difficulties with the show’s marketing material, and the disappointing lack of interest in a theatre bus to provide transport for theatregoers.

There were, however, some successes. A relationship with local young people’s outreach organisation Soundskillz proved fruitful, with a group visit on the second night achieving good attendance. There are also a number of areas, such as the university, where definite potential has been identified, suggesting promising possibilities for the future life of the NTiYN project.

Key Findings – Building Conversations

The results of NTiYN’s attempts to engage new audiences in these first six months were largely successful, with the Audience Agency concluding that “NTiYN undoubtedly achieved significant new audiences”. According to the Audience Agency’s evaluation, at least 25% of those attending a NTiYN show were new to the venue they visited, while Fuel attracted at least 10% new audiences to every show on the tour. NTiYN was also shown to engage with some particularly hard to reach groups for the first time and the direct feedback from audiences was overwhelmingly positive.

I enjoyed the event very much! The venue is great and the effort to put ambitious performances on in Preston is much appreciated.

Audience member at The 14th Tale, The Continental

It was an amazing piece in an unusual setting. Not what I was expecting but a lovely surprise. Loved it!

Audience member at Love Letters Straight From Your Heart, Lakeside Theatre

This was my first experience of this type of performance. I though the first few minutes came across as pretentious but was soon won over by the honesty and humour and emotion. The stories told weren’t outlandish or extraordinary but were told with grace and power.

Audience member at The 14th Tale, The Lighthouse

Really enjoyed the show, a breath of fresh air for Malvern and just what is needed to attract a different audience.

Audience member at The Victorian in the Wall, Malvern Theatres

While these audience development results are encouraging, there were also several other outcomes from this six-month research project. As the case studies from Poole and Preston begin to suggest, there are a number of important lessons to be taken from this early phase of the scheme and carried forward as NTiYN continues to develop. While there are many different findings, these can broadly be divided into two key categories: collaboration and planning.

As already identified, one of the problems that the touring model often faces is the failure of companies, producers and venues to work together successfully. Where audience development initiatives have been most successful, there has been open and productive collaboration between Fuel, the venue and other local organisations. Equally, on the few occasions when these relations have broken down it has caused problems.

In terms of collaboration, the appointment of a suitable LES is vital, as they are able to play an essential role at the centre of the many relationships involved. The LES’s local knowledge has in many instances proved to be deeply valuable, while clear communication between the LES, the venue and the NTiYN project manager is key. One particularly successful model was that in Malvern, where an LES was paired with an employee at the venue. Malvern Theatres found this to be an extremely positive partnership, once again highlighting the value of collaboration.

The concept of providing additional support to a venue through the employment of a locally based LES was viewed very positively as a strong approach to reaching new communities and groups. The fact that this person came with their own contacts and skills and was ‘independent’ of the partner venue was also commented upon as very useful.

Audience Agency Evaluation Report

Planning, meanwhile, has emerged as a decisive factor in determining the likely success of audience development efforts. There have been a number of issues around timing, such as difficulty with scheduling workshops around artists’ other commitments and programming conflicts with other events in the area, which could in most cases be avoided with more comprehensive planning in the early stages of the project. Despite students being highlighted as a target demographic, several shows coincided with university holidays; elsewhere, there were frustrating missed opportunities, such as a comedy festival in Colchester that would have been an perfect fit with The Victorian in the Wall.

What these examples illustrate is the importance of a holistic planning process with greater lead times, working closely with programmers to eliminate any scheduling clashes and drawing up plans for audience engagement activity from the moment a project is given the green light. This is reflected in the feedback from the Audience Agency, who have recommended “taking a more informed approach to planning particularly around timescales”. However, it is unsurprising that there were some issues with planning given the considerable ambition of NTiYN and the exploratory nature of this research phase, and the intention is that these findings will inform the next stage of the project.

A number of the NTiYN findings correspond with the experiences of other touring companies, producers and venues. Just as conversations around this first set of shows have revealed some of the potential problems with the ways in which work is being marketed to different audiences around the country, Gavin Stride emphasises the need to rethink how audiences are communicated with. He argues that more work needs to go into making companies understand that “what they might think makes their show sound esoteric and clever in their world isn’t necessarily the same language that needs to be used to get a show to an audience”. Through the research phase of NTiYN, Fuel are beginning to learn what marketing material is most likely to reach and engage audiences, with the video trailers for each of the shows proving to be particularly successful.

There is also a widely recognised need for “bespoke planning”, as David Jubb puts it, acknowledging and adapting to regional differences. This planning includes a course of action for engaging with both the receiving venue and other organisations in the area, encouraging greater collaboration. As well as more obvious ways of working together, such as sharing of audience data and getting the venue staff behind the work, this collaboration can stretch even further. Jo Crowley, for example, says that a “cross-marketing effort would be useful”, connecting arts networks across different genres to reach people who might have an interest in the work – a strategy that Fuel are beginning to develop through the strength of the LES model.

In terms of audience development, there are a number of strategies that keep reappearing in different guises. Returning to the same areas to build an audience, as Fuel intend to do, is important; Hanna Streeter, an associate producer with Paines Plough, has observed “dramatically” increased audiences in areas that the company has kept going back to. This in turn has a knock on effect for those venues’ programmes throughout the rest of the year. As Fuel and others have discovered, direct contact, conversations and word of mouth cannot be underestimated.

When we return to each of these places, we hope that people there will have made a connection and will maybe have been to see one of the shows and say ‘that’s by Fuel, I don’t know this new artist that they’re bringing, but I’m going to go because it’s a Fuel produced event’. And we hope that by having a deeper engagement with the people that live in these places that will be possible, not only for what we produce, but for the wider theatre landscape.

Louise Blackwell, co-director of Fuel

It is also important not to underestimate the gamble that companies are asking audiences to take on their work. As squeezed budgets makes the purchase of a theatre ticket a relatively significant financial decision, perhaps theatres need to find ways of minimising the perceived risk for audiences without making the work artistically conservative. This might mean remounting work that has already been successful elsewhere, as ETT are doing, or it might mean offering audiences added value with their ticket, like the Theatre Club and Theatre Salon events. And, as a number of different individuals stress, these initiatives should all be executed with the aim of building shared audiences for the future. As Caroline Dyott points out, creating a sustainable audience appetite for this work in the long term has to be the aim.

At the heart of all these tentative lessons is the need for collaboration and dialogue. That can be with and within venues, with local arts communities, with audiences, between different touring organisations around the company. Ultimately it is about people and about relationships. As well as the necessity to work together in order to make any given touring project work, the myriad issues that the UK touring model currently faced are perhaps best overcome through shared learning.

It all starts with conversation.

Sources

Interviews with:

- David Jubb, artistic director of Battersea Arts Centre

- Caroline Dyott, associate producer, English Touring Theatre

- Ed Collier, co-director of China Plate

- Gavin Stride, director of Farnham Maltings

- Jo Crowley, producer, 1927

- Hanna Streeter, assistant producer, Paines Plough

This report was commissioned by Fuel as part of the New Theatre in your Neighbourhood project.